It’s a viscerally emotive picture. A woman who appears to be pregnant lies on the floor of a subway station. It was taken on July 21, after a mob attack in the Yuen Long district of Hong Kong left at least 45 people injured – including the woman, a civilian who had been caught up in the attack and became known locally as “the woman in white” or “big belly lady,” slang for “pregnant lady” in Cantonese.

On social media, posts alleging that she had suffered a miscarriage were shared thousands of times. As more footage emerged, public outrage intensified over the Yuen Long violence, and towards the police for their alleged failure to protect victims from the baton-wielding attackers, who appeared to target protesters returning home from a march.

But then came the counternarrative. She wasn’t pregnant, people claimed, and her alleged miscarriage was a politically motivated rumor.

Though local media claim to have confirmed her pregnancy and the safety of the baby, the truth remains contested. Either way, the incident clearly illustrates the power of unverified online rumors to shape the narrative driving the city’s worst political crisis in decades.

Mass protests began more than two months ago over a controversial bill which would allow residents to be extradited to face trial in mainland China. The bill has since been shelved, but the uproar stoked a wider civil unrest that shows no sign of abating.

On the streets, protesters and police face off each week with escalating violence. Online, an equally bitter battle is being waged using the weapon of misinformation.

Just like the protests and clashes, fake news is threatening Hong Kongers’ unity and safety – and there is no end to it in sight.

How fake news spread and spiraled

In Hong Kong, there’s virtually no way to avoid misinformation.

In the subway, fake news is anonymously AirDropped onto commuters’ phones. Rumors and speculation posted by both individuals and local blogs are plastered over Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and shared on messaging apps such as WhatsApp and Telegram. Their controversial content is the topic of daily conversation citywide.

The rumors that take hold often prey on pre-existing fears and paranoia – and are just believable enough to work.

“We all have a cognitive tendency to believe what we want to believe and dismiss what we don’t want to believe, without any evidence that suggests what is true and what is not,” said Masato Kajimoto, a journalism professor at Hong Kong University, who specializes in misinformation.

In one viral tweet, for example, an unverified user warned the Chinese military was about to cross the Hong Kong-Shenzhen border to wage a Tiananmen Square-style crackdown, with an accompanying video of tanks at a train station.

But a station sign in the video reads “Longyan” – which is not in Shenzhen, and likely refers to a city in Fujian province, hundreds of miles away. Fact-checkers online pointed this out, but it was too late – the video has now been viewed more than 848,000 times and has more than 8,000 retweets.

The tweet tapped into a powerful fear that underlies the ongoing political crisis – that Beijing is encroaching on the unique freedoms of this semi-autonomous Chinese city. As a former British colony, Hong Kong enjoys protected freedoms of speech, press, and assembly, as decreed when Britain handed the city back to China in a model of governance called “one country, two systems.”

Now, young protesters feel like they’re running out of time to achieve full democracy before the looming deadline of 2047, when Hong Kong is set to become fully reintegrated with Xi Jinping’s authoritarian mainland China.

To many, it doesn’t matter that Hong Kong officials have called rumors of Chinese military deployment “totally unfounded.” Once the rumors begin – even if proved fake – they sow lingering seeds of mistrust, especially towards the government, which protesters accuse of inaction and bending to Beijing’s will.

Narratives of Chinese intervention are “actually from an old playbook,” Kajimoto said. Similar rumors circulated in the 2014 Umbrella Revolution.

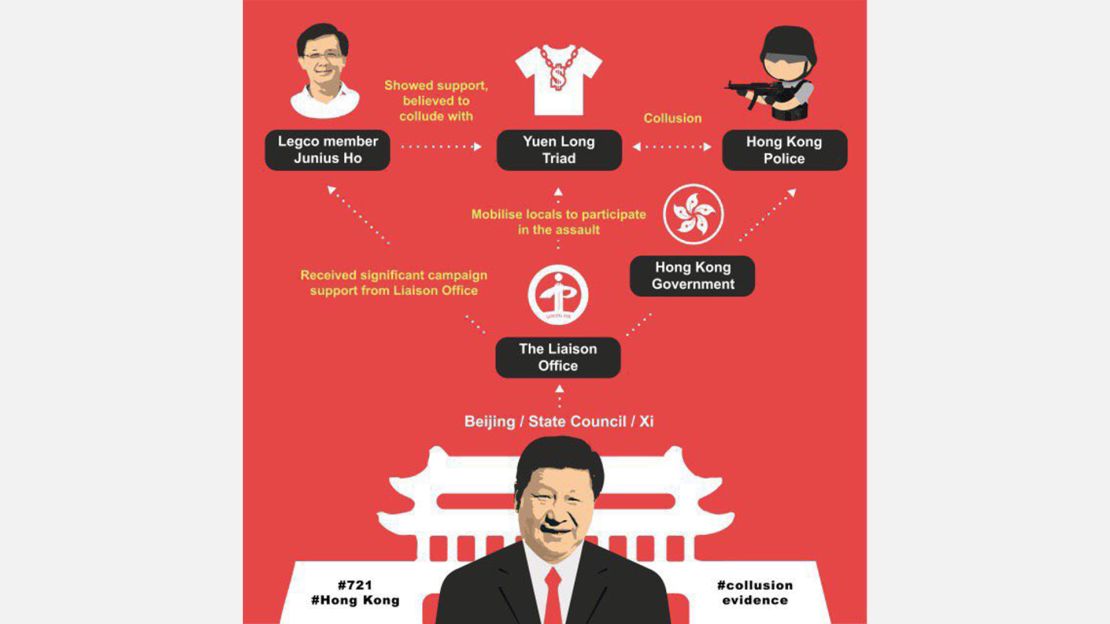

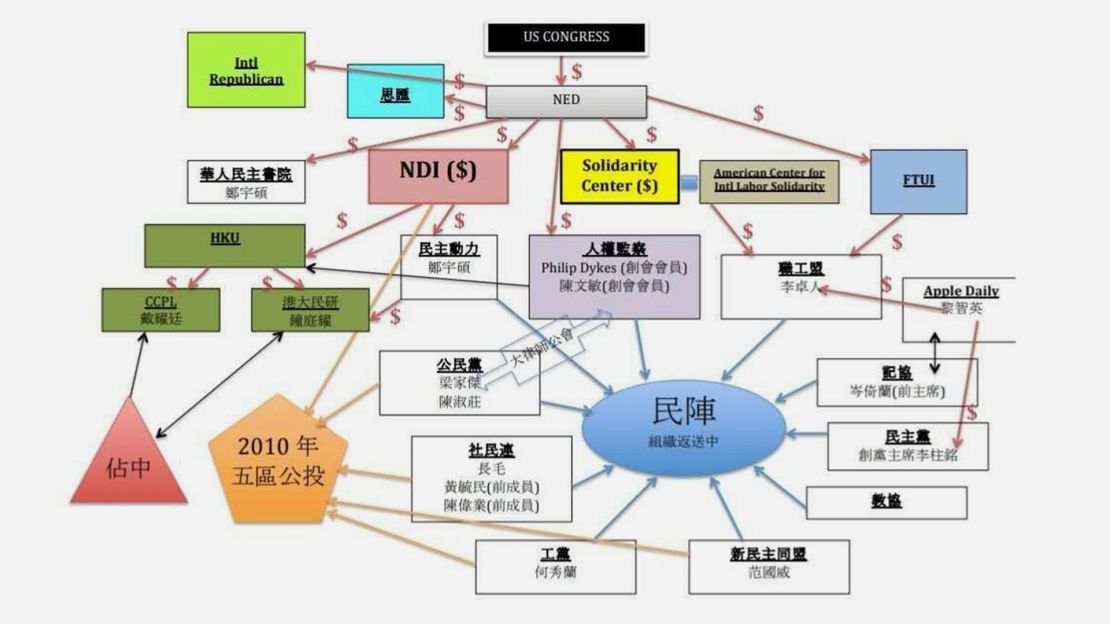

Another long-standing rumor to have reemerged is that of US interference in the protests. Elaborate conspiracy maps have circulated among those who oppose the protests, purportedly showing how US government agencies are funding the protesters. Meanwhile, photographs have been shared of Caucasian men at the protests, labeled as secret CIA agents responsible for orchestrating the unrest.

Even the mainland Chinese authorities have accused the US of influencing the protests. “As you all know, they are somehow the work of the US,” Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying said of the protests last week.

Beijing has not yet provided any evidence to back these allegations – but for many online, the photos of so-called CIA agents seem like proof enough.

The cycle of mistrust and misinformation

It’s unclear where many of these rumors begin – partisan groups, internet trolls, state actors? – or whether they are just innocent mistakes. Tracing their origins would require a team of data researchers to monitor the influx of social media content, said Anne Kruger, an editor at First Draft, a non-profit that fights misinformation globally.

But an organized fake news campaign is “certainly a possibility,” she said, adding there have been some telltale signs of this. Kruger has observed pro-Beijing accounts popping up on Twitter with zero followers, seemingly set up to send death threats to pro-Hong Kong protest leaders in Australia, where Kruger is based.

“That signals to me a campaign – but how organized it is, is hard to say,” Kruger said.

One thing seems clear – in an already divided society, misinformation and polarization are feeding off each other in a vicious, self-perpetuating cycle. Misinformation itself is “a manifestation of polarized society,” said Kajimoto. “The political division is the very reason why many people are believing, sharing and spreading manipulated content to begin with.”

The reason division breeds fake news is simple, said Kajimoto – people believe what they want to believe, and dismiss what they don’t want to believe, regardless of the evidence. This is especially true in times of crisis, when people cling to their beliefs more tightly in the face of opposition and threat.

At the same time, misinformation is deepening an ideological rift that has existed for years. With violent clashes becoming the new normal, the Hong Kong protests are turning parents against children, friends against friends, the youth against the government, and civilians against police.

This polarization isn’t limited to individuals: it has also fed a growing perception that local media outlets are biased either for or against the protesters. Many young Hong Kongers, like 21-year-old Ava Leung, gravitate towards news sites like Stand News and Apple Daily, which are typically more sympathetic to the protest movement. Meanwhile, those who oppose the protests – for example, Leung’s parents – tend to rely on broadcasters like TVB, which she characterizes as pro-Beijing and “not accurate.”

This declining faith in the objectivity of local news media has, in turn, led people to rely more on social media for their news, opening up space for online rumors and misinformation to spread.

Some are aware of the danger of misinformation and take precautions – several young Hong Kongers interviewed for this piece said that when they read rumors online, they cross-check claims with a variety of local and foreign media coverage, try to locate the information source and spread the word if something is found to be false.

“From my heart, I want to find the truth, to tell people what is true. Even the people by my side – I don’t want rumors or untrue things to affect us,” said Mixe Lee, a flight attendant from Hong Kong. “The environment and the atmosphere are already very serious, so it’s very important to clarify if things are correct or not.”

Chrysilla Joy Villanueva, a 21-year-old student, said she never reposts information without verifying it first, and urges others to fact-check online rumors.

But not everybody is as cautious. People often share misinformation “without even giving it a thought,” Villanueva said. “That’s the thing with social media now. If people send stuff like this, you instantly believe it.”

A city shadowed by fear

In Hong Kong, as is the case worldwide, misinformation online can result in consequences beyond ideological confusion.

One video that went viral on Facebook shows a Caucasian man at a July 14 protest moving his hand along his lower torso. The post claimed the “secret hand signal” proved he was an undercover foreign agent. The video, hashtagged #CIA, has been viewed over 40,600 times.

The man, in fact, is a well-known Twitter user who said the “hand signals” had been him pulling his sweaty shirt from his body – but the damage had been done. The furor had reached his employer, he said, potentially jeopardizing his job.

The rumors are also threatening people’s physical safety and sense of security. For instance, some people online have speculated that criminal gangs, known in Hong Kong as triads, had hired members of ethnic minorities to attack protesters in Yuen Long. Ethnic minorities, particularly those with darker skin, already face a certain amount of prejudice in Hong Kong – now, some feel they are being viewed with greater suspicion.

“I’m already afraid of going outside – especially now that the rumor came out,” said Villanueva, who is of Filipino descent. As a young woman, she doesn’t look much like a hired thug – but with heightened racial tensions, she fears possible public confrontations.

“I get stares from locals,” she said. “I feel like I have to be careful out there even though we’ve done nothing – we just look different.”

Misinformation experts like Kruger are bracing for a potential escalation in the online rumors, which would see the posts not simply report news but also include “calls for action and retaliation.”

This has already happened to deadly effect elsewhere. India saw a spate of mob killings in 2018, sparked by rumors of child abduction on WhatsApp. In some cases, the victims were lynched by crowds of almost 3,000 people. Meanwhile in Myanmar, misinformation fed alleged genocide. Hatemongering Facebook posts and viral fake photos targeted the Rohingya Muslim minority, who were persecuted in what the UN calls “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing.”

Online rumors have also spawned real violence even in the United States – take Pizzagate, the infamous 2016 case where a man fired a rifle inside a Washington D.C. pizzeria because of an online hoax that claimed the pizzeria was running a pedophilia ring that somehow involved Hillary Clinton.

There is no suggestion that Hong Kong is at imminent risk of this kind of fatal, mass violence – but Kruger warns that with “heightened emotion” across the city, “nobody is acting in a calm manner and that’s the danger.”

The way forward

As the rumor-driven killings in India and elsewhere have shown, misinformation – and the violence it incites – is a global problem. Countries and companies worldwide are responding.

Governments in Australia, Nigeria, Canada, to name a few, are carrying out public awareness and media literacy campaigns, teaching people how to spot and avoid fake news. Many of these tactics include measures described by Villanueva and Lee, including cross-checking with other outlets and staying wary of sensationalist headlines.

Meanwhile, some countries like India and Sri Lanka have resorted to shutting down the internet at times to halt the spread of fake messages.

Facebook has launched an anti-misinformation campaign, tweaking site features to limit the reach of fake news and hiring fact-checking moderators around the world. WhatsApp has also introduced new anti-misinformation features, including limiting the number of times messages can be forwarded.

But significant change has to come from the ground up, starting with public education on spotting fake news, said Kruger, who has pushed for mandatory media and news literacy programs in schools in the Asia Pacific region.

Until then, the public should simply exercise more caution and take news with a grain of salt.

“If something looks not really verified, they should simply ignore it. Don’t give any oxygen to it and amplify the message,” said Kajimoto.

“If that information or rumor still goes viral and many people are discussing it, then journalists or other concerned citizen groups will start investigating it; sooner or later, they will find out if the story is true or not. Most people can wait until then.”