In Hong Kong, we see Pakistan-India hatred for what it is

- An Indian journalism student meets a fellow student from Pakistan and finds that when living in a land far away, borders hold little meaning

“As an Indian, what’s the first thing that comes to your mind when you hear the words India-Pakistan?”

For a moment, I was at a loss for words. I barely knew Abdul. We had only met a few hours back at an event organised by the South Asian Society at the University of Hong Kong (HKU), where we are both students. The queues for food at the event were long and both our groups of friends decided to head out to look for dinner together.

As we walked the streets of Kennedy Town for food options that met our shared “spice-centred” taste buds, I told Abdul it has always been a dream for me to see Pakistan.

He paused, confused by my answer. “Really? For you, a journalist, I think it will be difficult to fulfil that dream.”

I could understand his curiosity. We have both grown up seeing hate messages for each other’s country. They are everywhere: in the newspapers, on television, on the streets.

In Muslim-majority Pakistan, the city of Mithi is a rare oasis of ‘love and religious harmony’ with Hindus

For me, it is a different story. My grandmother, a refugee, had lived in Sargodha – now a fast-growing city of about 650,000 people in Punjab, Pakistan’s most populous province – before lines were drawn between India and Pakistan in 1947.

A farmer’s daughter, my then 13-year-old grandmother was among the last to board a refugee train to India during Partition. Her Muslim neighbours urged her family to leave and save their lives as the violence surrounding Partition intensified. Her eyes would fill with tears whenever she talked about her childhood in the Motia Bagh area of Sargodha, where the women cooked for the whole community.

We still remember the taste of her home-made Indian bread, known as tandoori roti, and still treasure that old clay oven she bought in India.

During the many summer holidays spent with my grandmother, I had heard many stories about a time when there were no differences between Hindus and Muslims. I still remember the glow in her eyes as she narrated the stories of one community, not Indian or Pakistani, opening their homes to one another and sharing delicious curries and snacks every night.

In historic first, a Hindu woman has been elected to the senate in Pakistan

Growing up in India seeing and witnessing all kinds of prejudices, Abdul’s question reminded me of a conversation I had with a group of Pakistani students on campus a few days back.

As a journalism student, our first assignment was to interview strangers on campus who could not be from Hong Kong or our own country.

I encountered a group of boys from Pakistan in one of the university canteens and approached them with a notebook and pen in hand, asking: “Do you read news from your home country?”

Immediately I sensed they were reluctant to talk to me. One of them whispered: “Let’s get out of here.” One hung back, showing signs of interest in responding, but his friends ushered him away.

“We do not read any news, we’re very busy, sorry,” he said to me politely as they left.

I found alternative interviewees from France, Greece and the UK and finished the assignment. But the reticence of those Pakistani students never left my mind.

I began to wonder: Where do borders exist? Are they just on maps? Or are they also in the minds of people?

Ahead of Partition anniversary, history textbooks are new battleground in India, Pakistan

Back at the dinner, Abdul instructed the elderly waiter: “Add eight butter naan and tandoori rotis.”

It was not at all difficult for our hungry group to choose the dishes on the menu as we had a shared love for butter chicken, lentils and spicy okra.

Over dinner, we spoke about what it was like to grow up in India and Pakistan. Abdul, a final-year engineering student, said he wanted to take the skills he was learning back to Pakistan after working for some years in Hong Kong. We talked about how we missed our families, the luxuries of cheap and delicious food in our countries, and also about the struggle to survive in the “matchbox rooms” of Hong Kong after having lived in spacious houses all our lives.

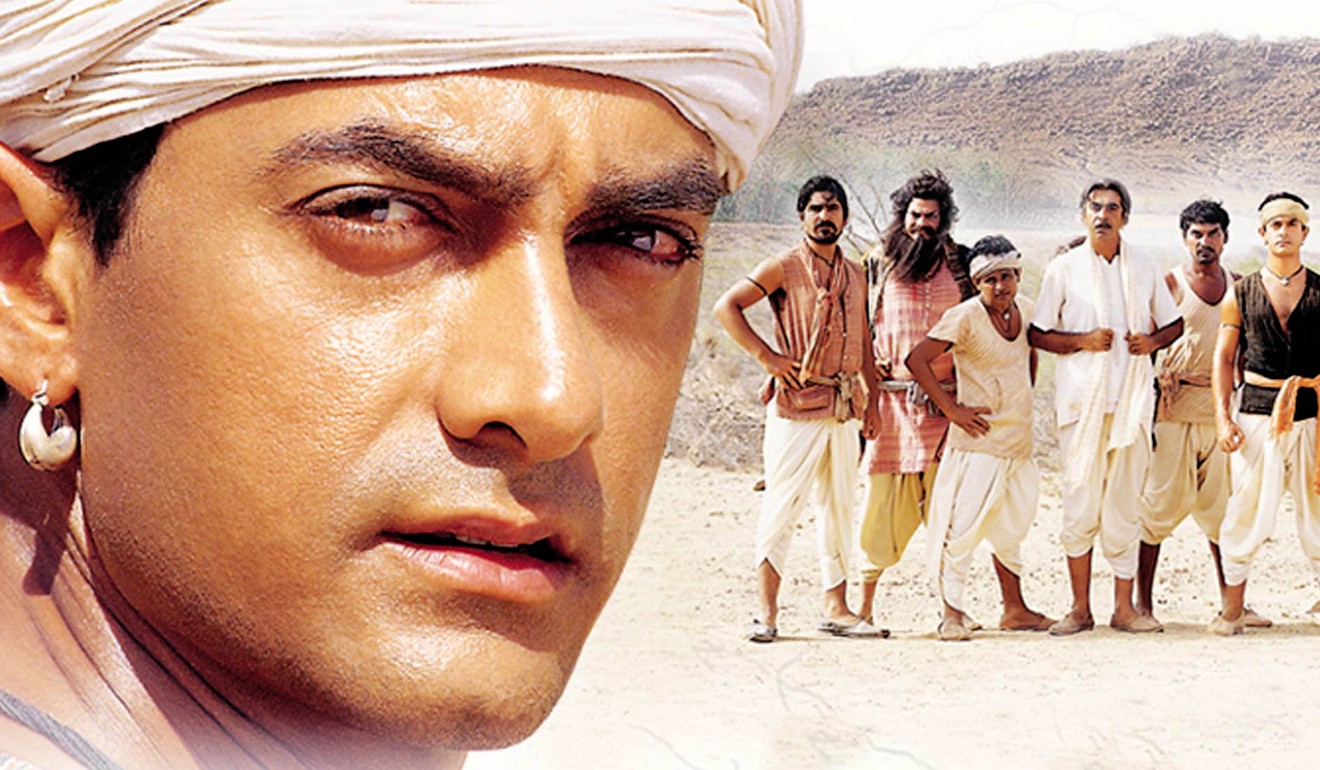

As we moved on to chai at a Nepali store after dinner, Abdul and I discussed politics, Pakistan’s elections, Indian prime minister Narendra Modi, and how the Pakistani students had seen all the classic Bollywood movies, including Lagaan, Main Hoon Na and Kal Ho Na Ho at least four or five times.

I cracked up as he talked about the epic family drama Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham, a love story that stretches across generations, describing the whole plot, every song and every piece of dialogue with meticulous detail. I stood laughing as he imitated a scene in which the lead character transforms from a shy teen to a heartthrob in an instant.

I was further amazed by my new Pakistani friend’s knowledge of the entire Indian national anthem, just from hearing it in movies and cricket matches. We also had a good laugh about the ritual border-closing ceremony at Wagah, where Indian and Pakistani troops goose-step wearing ridiculous hats try to outstare and outshout each other.

Floods to farmer suicides: for Pakistan and India, real threat is the weather

It was this cultural night that made me realise that when you move away from your home country, it is easier to focus on one’s similarities. Only then do you realise those similarities outweigh the differences.

Here at HKU, I see that shared bond my grandmother talked so fondly about. The Indian and Pakistani students here play Monopoly and even cricket together as one university team. They live in the same halls, share deep bonds of friendship and care for each other.

The students are fully aware of the political tensions. “When we are studying or spending time together, we make sure not to bring the Kashmir issue in our talks and gracefully avoid talking about it,” Abdul said, referring to a long-standing disputed border state that has provoked several wars and numerous skirmishes.

“But, nothing beats the fun we have watching cricket matches together,” he said.

It was years ago that India and Pakistan decided to part ways. Lines were drawn on land and water. But, meeting these strangers-turned-friends, I realise, in a land far away, these borders do not hold much meaning for so many.

After all, India and Pakistan started our journeys together as one. Two countries with large populations, sharing the same skin colour, eating virtually the same food rich in spices and flavour, speaking similar languages and living under the same sky. We even face the same problems such as poverty, illiteracy, gender discrimination and hunger.

For me, the geographic borders of India and Pakistan do not mean much, and never will. As the Lunar New Year beckons, and many Chinese students prepare to head home, Abdul and I plan to get our South Asian and international friends together at Hong Kong’s beaches and bond over some “home-style” food, drinks and movies that we share.

Supriya Batra is a master’s degree student at the Journalism and Media Studies Centre at the University of Hong Kong